Have you ever wondered what a security researcher does all day? From investigating malicious software to social engineering, security research is more than a full-time job - its a way of life. In the past year, we’ve seen security research hit the mainstream media as more organizations continue to get hit with malware, botnets and more.

Today I sat with Bill Smartt, Security Researcher for AlienVault Labs, to find out more about what it takes to become a security researcher in 2014...

How did you go about becoming a security researcher?

I studied computer science at the University of San Francisco to get a baseline understanding of how to think in an algorithmic way to solve problems. Prior to graduating, I was participating in an assembly class learning about Linux system calls. During this class, we found that after a user logs out, the network cards in the lab computers weren’t flushing out all the data in the Fedora Linux Dell desktop computers. What that means is if you logged in, opened a raw socket, and read from the network card buffer, you were able to read the network data from the previous user. Now, that’s not to say that we found anything “juicy” but it was an interesting vulnerability. What struck me was the way that my teacher continued the lesson without pause. It was in this moment that my red flags went up and my curiosity was sparked. Then in 2010, I went to my first Def Con in Las Vegas and my life was never the same…

What particular skills or talents are most essential to be effective as a Researcher? How did you learn these skills? Any formal training programs?

The most important tool for any security researcher is knowing how to effectively use google as a resource. The first part is knowing what and how to search and the second part is to absorb the information that is presented. This is the same skillset for any type of researcher - whether it be medical, financial or even market research. Most of my security education has been developed through self-directed learning. One aspect of security research (SR) that makes it challenging is the decentralized nature of resources. While security has become quite a hot topic in the media, much of the latest and greatest findings are concealed in (sometimes private) mailing lists, blog posts, IRC chat logs, and twitter conversations. Being able to hook into these conversations and being open-minded are essential groundwork for becoming a security researcher. The ability to use a computer for multiple hours at a time is also helpful. :wink:

What is a normal day like for you?

There is considerable time spent keeping up to pace with mainstream media, the latest threats on the internet, twitter, with short bursts of highly technical research in between. Leads to good research don’t always happen at 8:00am on Monday morning. Incidents happen when they happen and as a researcher you must love the chase enough to respond regardless of the time or day. So I guess the short answer is, there is no normal days.

What does your desk look like? E.g. what equipment are you using, how many screens do you have, etc.?

As many as my employer will give me (yes IT, I am looking at YOU!). Just kidding, I have an external drive full of VMs with full-versions of Linux, Windows - going all the way back to Windows 98. Dual screen monitors just to keep me busy and a really powerful laptop with a lot of RAM. I also have a book shelf lined with topics ranging from Computer Science basics to malware analysis and everything in between.

What tools do you prefer to use for your research?

Like most flavors of computer geeks, to each his own. Personally I use mostly OSX at the physical level. But as a security researcher, I probably spend just as much time inside virtual machines as I do my host operating system. One of my most prized tools is my wide array of virtual machines containing various versions of operating systems, language packs, service packs, kernel versions, and architectures. Having these different environments on hand to experiment with is very helpful when observing the behavior of malware.

Additionally, I try to use every sandboxing service that I can - You can’t really trust one sandbox, so its always good to check as many as possible. Having a wide array of accessible sandboxes is really important. I also use Pastebin from time to time if I’m researching a specific IP or strain of malware. But when it comes to free services, I spend most of my time on VirusTotal - a free service that you can use to analyze suspicious files and URLs.

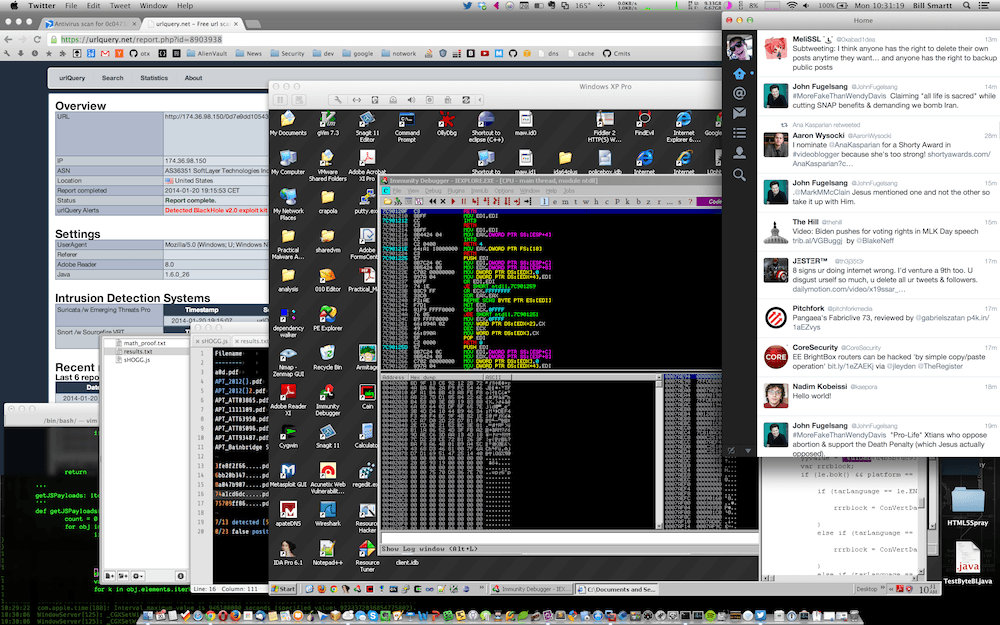

If I looked over your shoulder at any point in the day, what would I see on your screen?

Either a mess of data (i.e. packed code, binary, unknown encoding), notepad, or some online network utilities site. (see below)

Do you work with a team or mostly by yourself?

Research is typically done by individuals, however there is information sharing throughout the entire process. Unsolved leads don’t usually last long on the internet and it is often a race between researchers to publish results. This is the main reason for the sporadic nature of security research. If there wasn’t so much pressure to be the first, collaboration would probably be more prevalent, but in most research investigations, the benefit of collaboration doesn’t outweigh the time lost sharing intel. However, long-term investigations usually present more of an opportunity to collaborate.

What do you do when you’re not working? E.g. is this a 24-hour job and/or a hobby as well as a profession?

It certainly isn’t your typical 9-to-5. Leads happen when they happen and as it is with most types of published research, “the early bird gets the worm”. If you want to be successful in this industry, you need to live and breath security research. For example, I was recently on vacation with my family in Hawaii. Rather than kicking back with a good fiction novel, I spent hours reading a book on elliptic curve cryptography on the beach… This is more than a full-time job, its a lifelong passion for me.

What’s the typical process for evaluating a piece of malware?

It really depends on the context. If the goal is to perform ‘security research’, then any insight into the malware is considered to be progress. However most malware researchers follow leads for more specific reasons, for example if a researcher were trying to track down a particular malware author, he/she may only be looking for clues as to who wrote the malware and has no interest in what it actually does. So again, it really depends on two things: the goals or expected outcomes of the research and also, simply where the research takes you - sometimes you can identify the C&C infrastructure but not pinpoint the actual author.

What do you consider success as a security researcher? E.g. identifying the source of an attack, etc.

My only answer to this question as it is would be: it varies greatly. Most of the time, its simply being able to understand and draw conclusions about the who, what, when, where and why. Any information that you can gather beyond just “I got hacked”, is progress. The biggest force behind how success is defined is circumstantial to the researcher’s goal. For example, if you’re working for a company who is conducting investigations for internal Incident Response (IR), the goal is not only to identify the offender but also to prosecute if possible.

On the other hand, if you’re a security research hobbyist or newcomer, the goal is typically to gain credibility on Twitter. For me, the ideal situation would be able to identify the source, motivation, effects of the attack, and how they were able to pull it off… But that’s generally hard to do.

If you were a real alien, what would your spaceship name be and why?

I’m going to have to go with the “Silver Bullet” - I think the security geeks out there will understand why.