Passive voice in written communication is a huge part of the InfoSec world’s perception problem.

I get it, I mean, it’s not really your fault, right? Your 8th grade English teacher probably made you write that way, because it’s formal. Or because it’s proper. Or because you’d flunk the class if you didn’t (forgetting for the moment that hacking the grading system was trivial. Whatever.) And even though you’ve forgotten, ignored, or learned better about 99% of everything you learned in school, for some weird reason no one’s ever been able to explain to me, the majority of people writing technical content (not trained technical writers; those guys know better) cleave to passive voice like they cleave to no other rule ever in any other aspect of their lives.

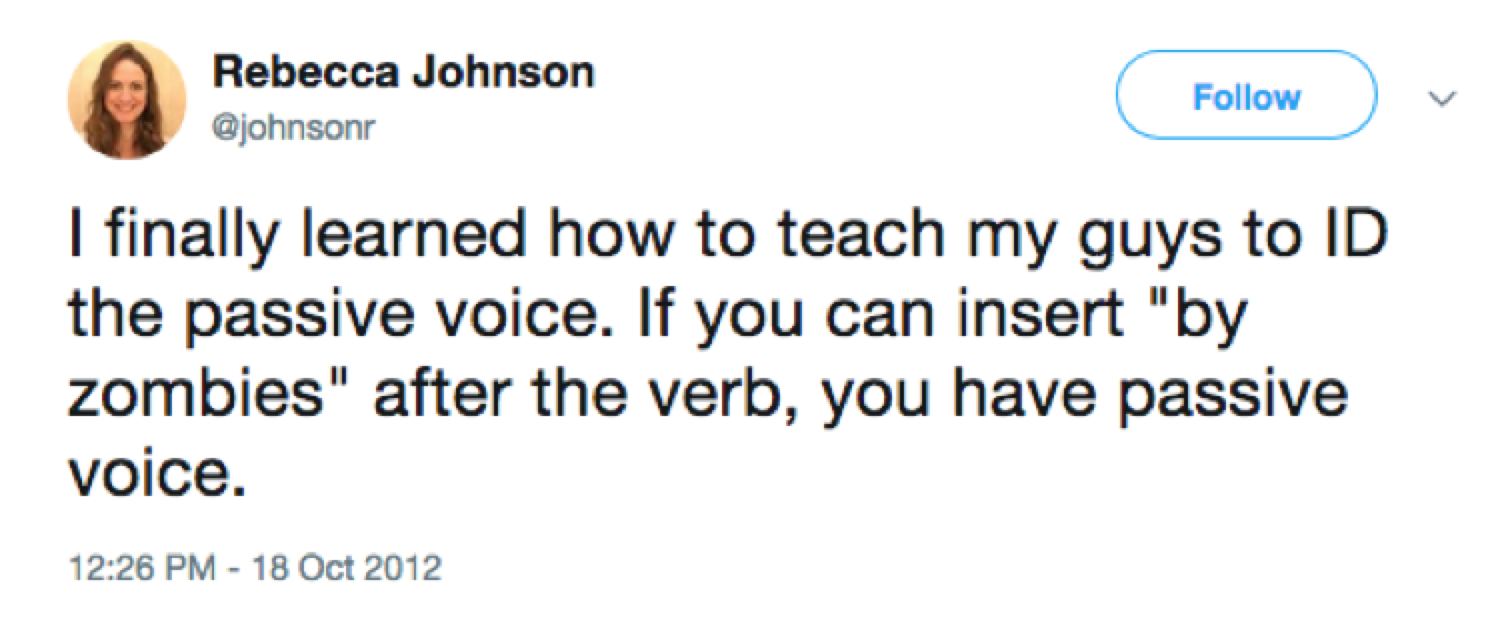

Not entirely sure what passive voice is? Merriam-Webster comes to the rescue:

Definition of passive

1 a (1) : acted upon by an external agency

(2) : receptive to outside impressions or influences

b (1) : asserting that the grammatical subject of a verb is subjected to or affected by the action represented by that verb

the passive voice

(2) : containing or yielding a passive verb form

c (1) : lacking in energy or will : lethargic

(2) : tending not to take an active or dominant part

Passive voice has a long and glorious history of being the language of plausible deniability, and of abdication of responsibility. It’s the language you used when you were four and got busted for eating the cookies. “Cookies were eaten.” It’s the same language that’s used when a politician gets caught doing practically anything. “Mistakes were made.” It’s a way of acknowledging that activity happened, without actually taking the blame for it, or ownership for the fixing of it. It’s the language of the shifty and has been for millennia.

“No one exists for even an instant without performing action. However unwilling, every being is forced to act by the qualities of nature” (Bhagavad Gita 3:5).

It is entirely fitting then, that this language is most easily identified by the following trick:

Ms. Johnson, Dean of Academics and Deputy Director of the MC War College, came up with this outstanding test back in 2012, as a way to teach Marines how to write more actively. Because who wants zombies in their writing? No one does. “Mistakes were made by zombies.”

But… hang on… why does the Marine Corps War College care about passive voice so much? Because passive voice introduces ambiguity into our writing. It makes it unclear to the reader who exactly did what and when. It confuses us about the differences between the actor, and the acted-upon. And in a situation where there’s an attacker and a target, ambiguity is the ultimate enemy, because people have to delay their response while they attempt to decipher the chain of causality.

I see passive voice in security writing all the time. Half the time, it truly sounds like it’s there to sound more formal, more astute. “The testing determined…,” “The phishing attempted to…,” “Control of the servers was lost,” “The defenses were breached,” “The machines were infected.” Who knows how these things happen, right? Just all of a sudden, bad things happened to good systems, and we’re not sure precisely by whom or why, but probably hackers, amirite?

When you’re creating critical security messaging, ambiguity can be fatal. If we’re hesitating because we’re trying to figure out who the zombies are, critical response time is wasted, and no one can afford that. Except the attackers.

The other problem with this language construction is that it makes it sound like these things are as big a mystery to you, the security professional writing the piece, as they are to the reader. No wonder despair sets in; if the professional has just been caught by zombies, what hope for survival is there for the rest of us?

So how do we fight zombies? With action, my friends. “The SOC team found the virus and immediately initiated quarantine procedures.” “The CISO authorized a security contractor to send phishing and spear phishing emails to the members of five internal email aliases.” “In their quarterly pentests, the IT team discovered eight unpatched vulnerabilities, and immediately installed the relevant patches.” Tell us who did what when, in a way that we can follow clearly. Let the reader feel secure in the knowledge that you are paying attention, conveying accurate information in a timely way, and eradicating the zombies.